Published on June 12 , 2019

IP policy matters – Why it’s a good time to update your IP policy

In today’s rapidly evolving intellectual property (IP) and knowledge exchange landscape, many IP policies that have been in place at universities and research institutions for years are at risk of becoming obsolete.

What constitutes a good IP policy in the evolving global landscape of knowledge exchange and commercialisation? How should a higher education institution manage and review their IP policy to ensure that it remains useable and relevant? IP policies are designed to incentivise the participation of the academic community in the commercialisation process, are you maximising your opportunities?

There is a well-established global interest in transferring knowledge and intellectual property (IP) from academia into the marketplace as a means of achieving greater social and economic impact. To successfully undertake this journey, a university needs a clear IP policy that outlines the ownership, management, and rules governing the use of their IP to the academic community as well as potential business partners.

Knowledge exchange and commercialisation is by its nature always evolving, and in recent years, what constitutes university IP for commercialisation has diversified. Traditionally there has been an emphasis on patentable inventions from STEM subjects. However, translation of IP and particularly non-patent IP from all research areas including the arts, humanities and social sciences (AHSS) as well as student-generated IP are increasingly becoming highlighted as important assets for higher education institutions to help realise social and economic impact. The explosion of data, databases, software and machine learning has also changed the IP landscape on many levels, including the legal implications of data commercialisation and the types of IP being commercialised from universities.

Governments have also increasingly recognised the value of university IP from across all academic disciplines. In the UK, the organisation UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) as well as national initiatives such as the Knowledge Exchange Framework (KEF) and Research Excellence Framework (REF) are shaping and enabling institutions to incentivise their academic communities to participate in the knowledge exchange and commercialisation process.

Universities typically review and update their IP policy every year in line with employment and IP law, as well as what funders and governments want to see. However, the evolving IP and knowledge exchange landscape means that many IP policies that have been in place at universities and research institutions for over ten years are no longer suitable. Without adapting to the changing ecosystem around them, these policies risk becoming obsolete.

What constitutes a good IP policy in the evolving global landscape of knowledge exchange and commercialisation? How should a higher education institution manage and review their IP policy to ensure it is useable, relevant, and incentivises the academic community to participate in the commercialisation process?

In a nutshell, what will a good IP policy do?

An IP policy is the essential component in an institution’s toolkit for knowledge exchange and commercialisation (KEC) and is the central document dictating all KEC activities. The policy will identify the types of IP that may develop from academic research at the institution, who owns this IP, how this IP is disclosed and protected, the range of activities that the institution can undertake to exploit this IP, as well as the rewards and incentives for the academic community to participate in this process.

“An IP policy provides structure, predictability, and a

beneficial environment in which enterprise and researchers

can access and share knowledge,technology and IP”

– WIPO (2019)

An IP policy must also complement the institution’s other related policies and procedures. For example, it must be aligned with the policy dictating the rules and regulations for academic consulting, as well as the processes and procedures adopted by the institution’s KEC office who will implement the IP policy.

How is a good IP policy structured?

Ultimately, an IP policy needs to be clear, appropriate, and therefore useable; by its research community to understand their role in the KEC process, by the KEC office managing the commercialisation process itself, and by the institution itself to ensure KEC activities are aligned with its wider mission.

Ideally, an IP policy is a concise stand-alone document. However, some universities chose to create separate policies for different audiences, for example one for students that details how the university’s IP policy affects them and what they need to do, and another for university staff detailing the terms and clauses for IP ownership and commercialisation that apply to them.

A good IP policy typically starts by outlining the purpose of the document, its objectives, and how it aligns with the institution’s mission for knowledge exchange. For example, an introduction could describe how the IP policy is designed to protect and manage IP but also encourage innovation and help meet the institution’s charitable objectives.

After a brief introduction, a good IP policy then moves to the various clauses, rules and regulations regarding disclosing, managing, and protecting IP generated by staff and students at the institution. IP policies need to be written directly for the academic community, with clear explanations of IP terminology. Some IP policies, for example the University of Manchester’s2, have accompanying guides that explain to researchers the different types of IP rights and how the commercialisation process works at the institution. Others, such as the University of Glasgow’s IP policy3, include a step-by-step flowchart of the commercialisation process from IP disclosure to how revenues are distributed once a deal has been made.

Finally, the language used in an IP policy may need to be adapted to account for changing trends in the IP landscape, for example where the arts, humanities and social sciences are increasingly recognised as important assets in the KEC process. To ensure KEC applies to a wide range of innovations and IP types, a good IP policy will keep its language up to date to reflect the innovation landscape and ecosystem. For example, an IP policy should move away from relying on terminology such as “invention” and “technology” and instead use “creative outputs” (University of Warwick’s IP policy4) as well as ‘creator’ and ‘creates’ (University of Cambridge’s IP policy5) rather than ‘inventor’ and ‘invents’.

What are the key clauses in a good IP policy?

Once an overall structure has been set, what are the main ingredients that go into an IP policy to ensure it achieves everything it is intended to do?

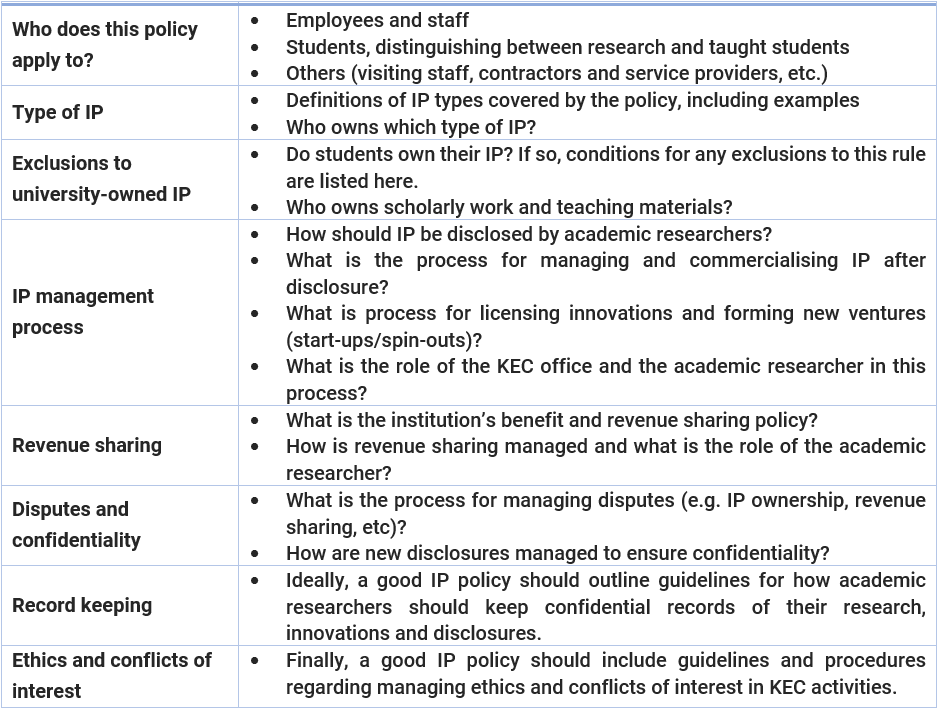

Each institution approaches this task slightly differently, but the key clauses in an IP policy are largely universal (Table 1). Regardless of its chosen structure, a good IP policy needs to clearly explain the types of IP that could come out of academic research at the institution, who owns this IP, how this IP should be disclosed and protected, the range of activities that the institution can undertake to exploit this IP, as well as the rewards and incentives for the academic community to participate in the commercialisation process.

Table 1: main clauses of an IP policy

What happens next?

What do you do after you’ve drafted a great IP policy?

Once written, an IP policy needs accompanying documents and guides that outline the processes and procedures for IP commercialisation at the institution. The IP policy and its companion documents also need to be effectively communicated across the institution to encourage the academic community to participate in knowledge exchange and commercialisation. However, research for the National Council of Graduate Entrepreneurship has showed that a university’s IP policy is typically unnoticed by the academic community6. To mitigate this, the role of the KEC office should be to ensure the IP policy and its key clauses are communicated to the institution’s research community, for example through clear disclosure of the commercialisation process in guides and marketing materials, as well as a through a range of training opportunities for academic researchers on IP and commercialisation.

Finally, an IP policy is never complete. It is a living document, one that changes in line with country law and evolves alongside the knowledge exchange and commercialisation landscape. In addition, as a KEC office matures and its activities become more established, a review of its institution’s IP policy and associated procedures will help to ensure that the types of KEC activities being undertaken by the office are accurately covered. An advisory committee of internal and external experts including lawyers, academic staff, and potentially external business representatives can help to manage this process; many universities have set up such committees to ensure their IP policies are in line with university strategies, processes and offerings, as well as national employment, finance, and IP law.

What are your thoughts? Head over to LinkedIn to join in with the discussion

1 WIPO (2019), “Intellectual Property Policies for Universities”, www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/universities_research/ip_policies/

2 University of Manchester, IP Policy Guide, https://umip.com/pdfs/ip_policy_guide.pdf

3 University of Glasgow, Policy for Intellectual Property and Commercialisation, https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_185772_en.pdf

4 University of Warwick, Regulations 28 Intellectual Property Rights https://warwick.ac.uk/services/gov/calendar/section2/regulations/patenting/

5 Statutes and Ordinances of the University of Cambridge Chapter XIII Finance and Property, https://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/univ/so/2011/chapter13-section2.html

6 UK IPO (2014), “Intellectual asset management for Universities”, www.gov.uk/government/publications/intellectual-asset-management-for-universities