Published on September 2, 2019

Looking outside the box: Creating value from Higher Education Institutions and industry relationships with open innovation

“No matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else”

– Bill Joy (co-founder of Sun Microsystems)

In the face of global challenges, why is it important for higher education institutions (HEIs) and companies to work together? In this article Oxentia’s Dr Richard Johnson discusses the opportunities and challenges of industry-academic partnerships. Richard has experience of working on both the university and industry side of the relationship and now works at the interface in knowledge exchange and commercialisation (KEC), otherwise known as technology transfer. He shares some thoughts on how both universities and companies can benefit from an open innovation approach, including collaboration, careful IP management, and strategic partnerships.

Companies like Procter & Gamble have increased research productivity by 60%, raised their innovation success rate to 100%, and at the same time reduced the cost of R&D by introducing open innovation into their innovation toolkit [1]. Open innovation allows companies to leverage the accumulated knowledge held by universities to build their R&D strategies, and universities to make their applied research more relevant to industrial challenges. For this to be a success both universities and companies need to build relationships less on a transactional basis and more as a partnership.

What is open innovation?

Organisations that practice open innovation look outside their organisation with a focus on collaboration; the emphasis for them is on ‘proudly found elsewhere’ rather than ‘not invented here’. Valuable ideas for open innovation are sourced from inside or outside the company in order to meet the needs of internal or external markets[2]. The benefits in collaboration and sourcing ideas from outside the organisation include lower costs, reduced risks and improved success rates [1]. The challenge here is not in problem solving (a traditional R&D activity), but in identifying and securing the intellectual property (IP) for a solution.

Universities are ideal partners for open innovation solutions as they aggregate talent and knowledge, reducing the effort required to find a solution. UK universities are also looking to collaborate with industry, driven by government priorities and the need to do more with decreasing levels of public sector income. Helping to connect these two groups is the expanding KEC profession. Collaborating through open innovation should be an attractive proposition for both universities and industry, at the same time making sure that IP is managed effectively.

There are myths on both sides that need dispelling; the most extreme of which are universities thinking companies want to take their ideas for nothing in return, and companies thinking universities want to publish all their confidential information. In my experience with university and industry relationships, universities usually are happy for companies to review and amend documents before publication to ensure IP integrity and will work to patent protectable IP before publication. Companies may also want to be co-authors on publications, delivering good marketing collateral and staff motivation.

Innovation in universities is not a one-off event, so companies want to be first to hear about new research and innovations, often looking to develop their research base by employing postgraduate and post-doctoral researchers from collaborating universities as potential new employees (as I once was). This is an attractive option for post-graduate and post-doctoral students looking beyond an academic career path. Most companies want to maintain a good relationship with universities. Dialogue between HEIs and partner companies needs to be open and sharing but making sure that all the legal boxes have been ticked.

IP Management and Exploitation

Successful open innovation relationships rely on good IP management. Henry Chesbrough, who coined the phrase ‘open innovation’ in his book Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology[2], said that IP is a key source of friction in open innovation relationships. IP only has value when there is a business model to exploit it. The first part of that business model needs to include the ability to capture and protect the IP. The second part of that model is to create and capture the value derived from the IP.

Conventional wisdom is that IP protection is used to control and exclude use of IP. Using an open innovation approach, companies or universities must create value from the IP they have generated (either through spinouts or new products) or allow someone else’s business model to do it for them (through licensing). People typically consider IP flow moving from HEIs to companies, but it also moves in the other direction, for example companies licensing new technologies for testing and feedback such as Oxford Nanopore’s MinION Access Programme [3]. Successful value capture and creation therefore relies on the ability to generate IP and have a business model to capture value from it. Universities are very good at the former whilst companies are very good at the latter.

IP generation, capture, and value generation are straightforward when everyone is working in the same team but not when working across different organisations, disciplines and industry boundaries. My colleague Dr Lauren Sosdian recently wrote about the importance of good communication for researchers [4] and the message is equally as important for building HEI and industry partnerships. In addition to communicating effectively, companies and universities need to work with similar expectations and to a similar framework.

For many universities, the technology transfer or the business support office provide the connecting business facing function. Ideally these offices will have standard operating procedures, documents and well-trained staff to support business interactions without having to draft and carry out legal reviews of contracts from scratch every time, which can take months to years. Tools such as the Lambert Toolkit [5] can be used to simplify collaboration agreements and standard non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and materials transfer agreements (MTAs) in line with good commercial practice make review and sign-off more straight forward.

Finding Partners

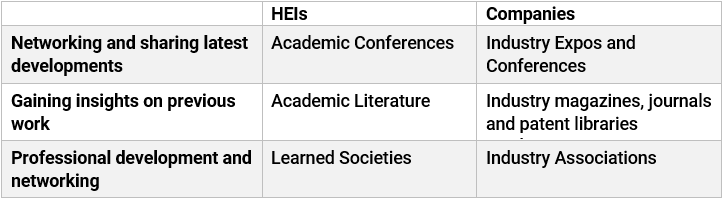

Universities and companies should see each other as strategic partners. It is important to understand each other’s strengths and weaknesses so that the partnership is complementary. Academics and researchers are a university’s ambassadors, and HEI-industry relationships cannot work without academic buy-in. However, in my experience, even when they are highly motivated to engage with industry, academics often network and source information in different places to industry researchers, as shown in the table below.

This means that encounters between the two groups can be infrequent, unless there are dedicated industry-academic conferences in a specific research space (a great example of this from my own technical background in oil field microbiology is ISMOS). Getting academics and industry researchers from the same subject area together in a room to talk about their research and interests is a great way to spark new collaborations which may lead to new partnerships. This needs a facilitator to take the responsibility and get people talking and planning.

Finding new partners means ’networking’, sometimes an enjoyable process, but for many, often viewed as a ‘job’. Typically this can mean meeting people through relevant conferences and workshops, leveraging existing contacts, technology scouting, building competency centres/centres of excellence, hosting accelerator programmes and crowd-sourcing innovation (for example Innocentive, Kaggle). Ultimately, the key is to develop relationships with partners and understand how each partner works. The partners need to agree a strategy to maintain regular contact and to build their relationship. This approach allows companies and HEIs to benefit from increased research productivity, reduced costs, increased innovation success rate, increased research relevance and increased career opportunities for researchers.

What’s your experience of working with universities or industry from either side of the fence? What things have worked well and what do you think could be improved? Get in touch or let us know in the comments on LinkedIn.

1 Ozkan, N. N. (2015). An example of open innovation: P&G. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1496-1502.

2 Chesbrough, H. W. (2006). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press.

3 Oxford Nanopore Technologies (2019) Company History. Retrieved September 2, 2019, from https://nanoporetech.com/about-us/history

4 Sosdian, L. (2019, July 24) Bridging the gap: why research communication benefits academia [LinkedIn Post]. Retrieved September 2, 2019, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/bridging-gap-why-research-communication-benefits-academia-sosdian/

5 UK Intellectual Property Office (2019) University and business collaboration agreements: Lambert Toolkit. Retrieved September 2, 2019, from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/university-and-business-collaboration-agreements-lambert-toolkit